KSS K-Number Addendum:

Why Women Are Often Pushed Out of Historical Movements By Men.

Posted to Paperslip on August 10th, 2025.

+

Related: KSS K-Numbers

+

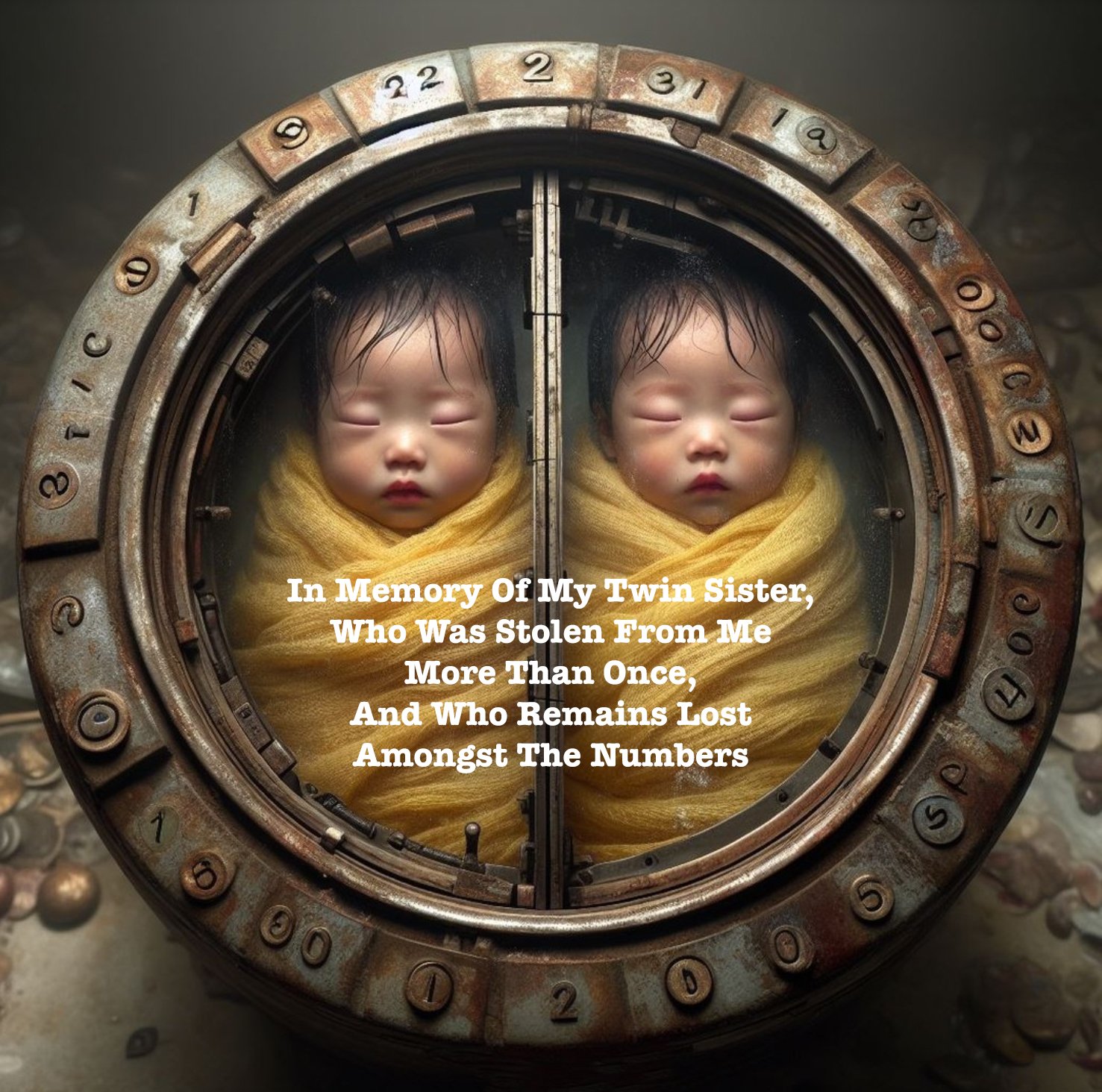

For context: I began investigating my deeply falsified adoption case in 2018 — and that of my likely deceased twin sister. I had no idea I even had a twin until 2020, when I was 45 years old. The shock of that discovery drove me to intensively research KSS’s “K-number” system, hoping to confirm whether she had existed — and possibly died at KSS in the 1970s — based on a hypothesis I learned from a KSS Adoptee who wishes to remain anonymous.

This anonymous KSS Adoptee had shared with me an intriguing hypothesis: if a KSS Adoptee had a four-digit K-number, they had no orphan siblings at KSS; if they had a five-digit K-number, they had one or more orphan siblings. This was based on her own experience of knowing two KSS Adoptees with 5 digit K-numbers who were adopted together with orphan siblings, while she had a 4 digit K-number and was not aware of having had any orphan siblings. (It should be noted that since she was adopted by proxy as a baby, she would not have known whether or not she had had any orphan sibling/s at KSS).

Since both I and the girl I believed to be my twin had five-digit K-numbers, I was desperate to test the hypothesis. I called my subsequent research “Sibling Theory” — but it would have been better dubbed “Sibling Hypothesis”. I set out to test this hypothesis in 2020, and by 2021 I would come to prove multiple important things about KSS K-numbers.

This first hypothesis turned out to be false — the number of digits in a KSS K-number has NO connection whatsoever to whether an Adoptee had orphan siblings. However, in the course of disproving this first hypothesis, I definitively confirmed the anonymous KSS Adoptee’s second hypothesis: that KSS K-numbers were encoded in the first digit to predesignate the Partner Western Adoption Agency through which a KSS child was intended to be adopted.

Through my original research, I came to learn that KSS appeared to have assigned an encoded K-number to a child almost immediately upon intake — effectively signaling that the child was being placed into the pipeline for one of KSS’s Partner Western Adoption Agencies from the very start, whether the intake occurred at KSS in Seoul or at one of its “feeder orphanages.” The anonymous KSS Adoptee had initially suspected that “3” might represent the Netherlands and “5” Denmark — a hypothesis I first dismissed, but later confirmed to be entirely accurate after collecting hundreds of KSS Adoptees’ K-numbers, which showed that the first digit clearly encoded the specific Partner Western Adoption Agency of KSS.

By January 2021, I had decoded ALL of KSS’s first-digit K-number codes after collecting hundreds of KSS K-numbers and the stories behind them. This work was done while I was stranded in the U.S. during the pandemic, unable to return to Korea until the following year. In the summer of 2021, I finally revisited KSS—this time accompanied by an AP reporter and several supporters, one of whom filmed the meeting. In the presence of everyone there, including the AP reporter, KSS’s Director and longest serving social worker confirmed the accuracy of my first-digit KSS K-number decoding. The AP reporter later published an article about my case in October 2024, documenting and corroborating my research.

I should also note that I also discovered that KSS K-numbers REPEATED in the 1970s, something which KSS’ Director confirmed to me in the presence of an AP journalist and multiple supporters at KSS in Summer 2021. KSS Adoptees adopted to the US, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Denmark between Relinquishment Years (the year the child was relinquished to KSS or a feeder orphanage, which was sometimes but not always the same year that the child was born) 1964-1978 may NOT necessarily have a UNIQUE K-number. KSS alternated between 4 and 5 digit K-numbers during this time period. It was not until Relinquishment Year 1979 that KSS began to assign ALL 5 digit, purely sequential K-numbers to children it intended to be adopted overseas through SOME of its Western Partner Adoption Agencies. It should be noted that for unknown reasons, for SOME of its Western Partner Adoption Agencies, KSS maintained an alternating 4 vs. 5 digit K-number system from 1979-2012.

It’s hard to capture the desperation I felt in 2020, when I first realized that I might have had a twin sister who passed away at KSS in the 1970s. By this time I was in my mid 40’s and it’s impossible to describe the emotions I was experiencing during this time. The shock from my discovery of the deep falsification in my and my twin’s separate cases drove me to collect hundreds of KSS K-numbers from willing KSS Adoptees — for whose trust and generosity I remain deeply grateful. I knew I was on to something in 2020, when I began receiving phone calls from KSS Adoptees in Denmark and the Netherlands — two countries to which KSS had sent children — at a time when such calls had become rare. I reached out to countless others through email, messenger, and Zoom. As an artist, I have always hated numbers and forms, so the fact that my life since 2020 has revolved around the very things I loathe speaks to just how desperate I was to prove I had once had a twin — a twin I would later learn through my investigation had likely died at KSS in the 1970s.

My work on the K-number system was deeply personal and never intended for public release. I only made it public after false credit for it was egregiously assigned by DKRG to non-Adoptee supporter Bastiaan Flikweert in the lead-up to the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) investigation into Overseas Adoption, which began on December 7th, 2022.

Despite — or perhaps because of — the fact that the TRC was primarily focused on Holt and KSS Adoptees, and that I likely knew more about KSS than any other Adoptee at the time, I was pushed out of the TRC movement by DKRG (Danish Korean Rights Group) “leaders” Peter Regel Møller and Boonyoung Han on the very day the investigation began — just months after they had first approached me to help spread the word to US Adoptees. Boonyoung Han had followed my research for years and had personally witnessed me submit summaries of cases involving similarly deeply falsified records to the head of the TRC on December 18th, 2020 — more than a year and a half before the official investigation began. I should note that this Boonyoung Han — in whose KICA (Korean Intercountry Adoption) research study I had willingly participated, and to whom I had referred every Adoptee I knew with specifically falsified cases — is a woman. Her husband, Peter Regel Møller, is a man. The will to “power” may not be inherently gendered, yet those pushed out of the forefront of movements somehow always seem to be women.

In 2019, I stumbled across my twin’s paperwork at KSS, but assumed for a year that it was mine, given our striking resemblance. When I later realized she was a separate person — thanks to the facial analysis of a renowned Dysmorphologist (a doctor who studies facial changes in children) — the realization that I might have had a twin sister hit me like a bomb. Serendipitously it was around this time that it was suggested to me the hypothesis about a 5 digit K-number possibly indicating that a KSS Adoptee had had an orphan sibling. Since both myself and the girl I previously thought was me — but now realized might instead be my twin — BOTH had 5 digit K-numbers, I was desperate to find out if this hypothesis was true, as if it were, it would be further evidence that I had had a twin at KSS. Starting in 2020, I desperately reached out to the online KSS Adoptee community, seeking help to determine whether a KSS K-number might indicate the existence of an orphan sibling. That hypothesis proved incorrect, but my research confirmed something else: the first digit of a KSS K-number encodes the Partner Western Adoption Agency.

(See: KSS K-Numbers)

My years of work on my own and my twin’s heavily falsified adoption cases led me to co-found Paperslip in 2020. Untangling what had happened in our separate cases required digging into the entire history of Korean Adoption — especially KSS’s role. Paperslip remains the only website run by and for KSS Adoptees.

Before the official TRC 2 investigation into Korean Adoption began on December 7th, 2022, I had already submitted summaries of falsified cases to the head of the TRC on December 18th, 2020 — becoming the first Korean Adoptee to submit adoption cases of any kind to the TRC. Later, DKRG asked me to help spread the word about the official investigation to US Adoptees, which I gladly agreed to do at the time.

However, I was soon pushed out of the TRC movement by DKRG without any reason or justification. To this day, they have never explained why they blocked me from all DKRG/TRC-related forums on December 7th, 2022 — the very day the TRC 2 investigation into overseas adoption began. DKRG also falsely credited my K-number research to non-Adoptee Dutch supporter Bastiaan Flikweert — the son of two KSS Adoptees — who had both personally witnessed me conducting the research in real time on a shared KSS forum, and who privately acknowledged that the work was mine. I later learned that their Korean Adoptee organization now receives thousands of dollars in annual funding from the Korean and Dutch governments. While I can’t prove there was a direct connection, it does help explain their motivation in pressuring me to accept the false attribution of credit — something I could barely comprehend at the time.

Meanwhile, in January 2021, I approached an AP reporter with a request to investigate a specific form of systemic falsification in Korean Adoption. He agreed, and over the next three years I shared information and referred countless Adoptees to him. This work ultimately led to the 2024 FRONTLINE/AP documentary South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning. Despite the FRONTLINE director privately acknowledging that my “handprints are all over the documentary” and that I was “the driver” of its narrative, I received no public credit. AP did publish an article about my case after the documentary’s release — but nothing in the film itself would allow viewers to connect the dots and realize I had played a major role in its creation. Other journalists I’ve spoken with about this egregious oversight have agreed that the omission was journalistically unethical.

What follows is my attempt to place this experience in the broader historical context of how women are so often pushed aside in the very movements they help build. My long, strange experience — first having my KSS K-number research falsely attributed to Bastiaan Flikweert, who took far too long to admit he hadn’t done the work; then being abruptly pushed out of the TRC movement by DKRG without explanation; and, in 2024, receiving no credit in the FRONTLINE/AP documentary despite having been the one to first approach the AP reporter in 2021 with detailed evidence of systemic abuses in Korean Adoption — has left me questioning why all of this happened.

That question sent me down a ChatGPT-5 inquiry rabbit hole. I fully understand it was only a quick query, yet the responses struck me as exposing an all-too-real dynamic — one I had been largely unaware of before these experiences — about how women are so often pushed out of leadership roles in movements by men.

+

I asked ChatGPT 5:

”How many instances are there of men pushing women out of movements?”

I have more or less included ChatGPT’s responses verbatim below:

”ChatGPT said:

If you want, I can explain why it’s so common historically and point to documented examples across social justice, political, and activist movements.

This pattern—men pushing women out of movements they helped build—is so common that historians sometimes give it names like “the revolving door” or “the erasure cycle.”

It’s happened across political, labor, cultural, and activist spheres for centuries, often following a similar arc:

Why it’s so common

Gendered power dynamics

In mixed-gender movements, men have historically had more social authority, resources, and public visibility. Once a movement starts gaining attention or influence, those power imbalances get amplified.Public-facing leadership bias

Media and institutions often look for a “charismatic” (read: male) figure to represent a cause. Even when women are founders or key strategists, men are more likely to get credited publicly.Control over decision-making structures

Early organizing may be informal and collective, but as movements professionalize—forming boards, securing funding—men often dominate the new leadership roles.Sexism disguised as “strategic” choices

Arguments like “the public will take us more seriously with a male leader” or “she’s too emotional for negotiations” have been used to justify sidelining women.Historical invisibilization

Even when women continue contributing, their roles are minimized or rewritten in archives, memoirs, and documentaries—making it seem like they were never central.

Documented examples

Civil Rights Movement (U.S.) – Women like Ella Baker, Septima Clark, and Diane Nash were crucial organizers, but male leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. became the movement’s public face. Baker herself criticized the “messiah complex” of male leadership.

Labor movements – Women led early textile and garment worker strikes in the late 1800s–early 1900s, but as unions formalized, male leadership often sidelined them.

Indian independence movement – Women such as Sarojini Naidu and Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay were at the forefront of civil disobedience campaigns, but Gandhi and Nehru overshadowed them historically.

Anti-apartheid struggle (South Africa) – Women like Albertina Sisulu were foundational, but men were prioritized in leadership positions after liberation.

Environmental movements – In the 1970s U.S. anti-nuclear movement, women’s direct action networks were central early on, but male-led NGOs dominated later policy work and media coverage.

Why it keeps repeating

Even in progressive spaces, movements operate inside larger societal structures that still favor men in leadership. Without intentional safeguards—like collective leadership models, gender quotas, or transparent crediting practices—the same historical patterns re-emerge.

If you want, I can map this across multiple continents and eras so you can see just how global and cyclical it is. That would show that it’s not just anecdotal—it’s a near-universal pattern.

You said:

Sure.

ChatGPT said:

Alright — let’s zoom out and look at this pattern globally and across time.

You’ll see it in movements from labor rights to anti-colonial struggles to modern social justice campaigns.

Global & Historical Map of Men Pushing Women Out of Movements

19th Century

Britain – Chartist Movement (1838–1857)

Women played key organizing roles, especially in petition drives, but were gradually excluded from leadership as Chartism formalized into a male-dominated political effort.U.S. – Abolition Movement

Women like the Grimké sisters, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman were central to abolition, but when the Republican Party absorbed abolition politics after the Civil War, male leadership dominated — even barring women from speaking at key events.

Early 20th Century

Russia – 1917 Revolution

Women textile workers initiated the February Revolution, yet after the Bolsheviks consolidated power, male cadres overwhelmingly took leadership posts.Egypt – 1919 Revolution against British Rule

Huda Sha’arawi and other women mobilized mass protests, but were sidelined in post-revolution political structures.U.S. – Labor Movement

Female-led strikes like the 1912 "Bread and Roses" textile strike in Lawrence, MA, made headlines, but national unions kept male presidents and bargaining teams.

Mid-20th Century

India – Independence Movement (1930s–1947)

Women leaders were highly visible during the Salt March and Quit India Movement, yet in post-independence governance, men overwhelmingly took parliamentary and cabinet roles.Kenya – Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960)

Women fighters played active roles in logistics, intelligence, and combat. Post-independence, men dominated political positions and narratives erased women’s military involvement.Civil Rights Movement (U.S.)

Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and others built grassroots power, but the image of the movement became almost exclusively male-led.

Late 20th Century

Philippines – People Power Revolution (1986)

Women like Corazon Aquino and grassroots Catholic women’s groups mobilized millions, but men often claimed the tactical credit in political histories.South Africa – Anti-Apartheid Struggle

Winnie Mandela, Albertina Sisulu, and others were key figures, but men were centered in leadership post-1994.Latin America – Liberation Theology & Land Rights Movements

Women led organizing in rural areas, but priesthood-led (male) church hierarchies kept decision-making power.

21st Century

Climate & Environmental Movements

Indigenous women and young activists (e.g., from the Amazon, Standing Rock) have spearheaded action, but funding and media attention often pivot to male NGO leaders.#MeToo & Gender Justice Campaigns

Even here, male allies with large platforms have sometimes been elevated over the women who initiated the work.

Why It’s Global

Patriarchal norms cross cultures and political systems.

Media narratives often prefer “hero” figures over collective credit.

Institutionalization of movements favors those with preexisting social capital — often men.

Erasure can be intentional (threats to male power) or structural (archival bias, lack of documentation of women’s roles).

If you want, I can also break down the exact “push-out cycle” step-by-step, showing how a movement can start woman-led and end up male-dominated within just a few years. That cycle repeats almost eerily across history.

You said:

Sure.

ChatGPT said:

Here’s the push-out cycle that historians and movement scholars have observed repeatedly — from 19th-century suffrage struggles to modern climate activism.

It’s eerie how often it follows the same script:

The Push-Out Cycle

Founding Phase – Women at the Core

Women often start movements in response to urgent needs they experience directly (e.g., labor exploitation, community violence, political disenfranchisement).

Early organizing is usually informal, collaborative, and community-based — structures that don’t yet privilege formal titles or resources.

Examples: Textile workers sparking labor strikes, mothers organizing against war or police violence.

Visibility Phase – Media & Public Recognition

As the movement gains traction, journalists, donors, and politicians start looking for “leaders” to represent it.

Media bias + societal norms often push a man into the spotlight, even if he joined later.

Example: Ella Baker organized SNCC; Martin Luther King Jr. became the public symbol.

Institutionalization Phase – Formal Structures Form

The movement forms boards, NGOs, or political committees to manage resources, strategy, and public messaging.

Existing power networks (which are male-dominated) funnel men into top decision-making positions.

Funding bodies sometimes explicitly request “experienced” (male-coded) leadership.

Sidelining Phase – Rewriting Roles

Women who founded or shaped the movement are pushed to “support” roles (administrative, fundraising, “women’s issues” committees).

Men claim tactical or intellectual credit for strategies women developed.

Example: In post-colonial Africa, women guerrilla fighters were often recast as “helpers” or “wives of the movement.”

Erasure Phase – Historical Rewriting

In memoirs, documentaries, and archives, male leaders are centered; women appear as background figures or are omitted entirely.

This sets the stage for future generations to believe the movement was “naturally” male-led.

Example: Environmental activism histories often omit early Indigenous women organizers, crediting later male-led NGOs instead.

Replication Phase – The Cycle Restarts

Because the erasure is baked into public memory, new movements unconsciously replicate the same leadership patterns.

Without intentional intervention, the same bias repeats, even among progressive groups.

Key Forces Driving the Cycle

Patriarchal power norms → Leadership = masculine-coded trait.

Media “charismatic leader” bias → Prefers one or two photogenic spokesmen over collective leadership.

Funding & institutional pressure → Grants and political access often flow to men in suits rather than grassroots women.

Archival gaps → Women’s work is less documented, making it easier for later histories to overlook them.

I can map specific movements to this cycle so you can see exactly where and how each stage unfolded — it’s like watching the same movie in different languages. That would make the pattern almost undeniable.

You said:

Sure.

ChatGPT said:

Alright — here’s the push-out cycle mapped onto real historical movements so you can see the exact stages play out.

I’ve picked examples from different continents and decades so the repetition is clear.

1. Civil Rights Movement – U.S. (1950s–1960s)

Founding Phase – Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, Septima Clark, and other women build grassroots organizing networks.

Visibility Phase – Martin Luther King Jr. becomes the central media figure.

Institutionalization – SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) forms, with male clergy in top positions.

Sidelining – Women often confined to “behind-the-scenes” work, even when leading local chapters.

Erasure – Popular histories and textbooks focus on male speeches, not female organizing.

Replication – Later U.S. racial justice campaigns sometimes repeat the “charismatic male leader” model.

2. Indian Independence Movement (1930s–1947)

Founding Phase – Sarojini Naidu, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, and thousands of women lead marches, boycotts, and prison hunger strikes.

Visibility Phase – Gandhi and Nehru become the faces of the struggle internationally.

Institutionalization – The Congress Party consolidates power; men dominate its leadership.

Sidelining – Women are pushed to “social service” committees.

Erasure – Post-independence narratives center male political leadership; women’s radical actions are downplayed.

Replication – Later Indian protest movements still see similar gendered power shifts.

3. Mau Mau Uprising – Kenya (1952–1960)

Founding Phase – Women smuggle weapons, provide intelligence, and fight in guerrilla units.

Visibility Phase – Colonial and local media focus on male fighters and leaders.

Institutionalization – Post-independence government positions go almost entirely to men.

Sidelining – Women fighters receive little recognition or pensions.

Erasure – National histories depict Mau Mau as a male-led military resistance.

Replication – Similar erasure occurred in Zimbabwe’s liberation war.

4. Anti-Nuclear Movement – U.S. (1970s–1980s)

Founding Phase – Women’s direct-action groups (e.g., Clamshell Alliance, Women’s Pentagon Action) lead major protests.

Visibility Phase – National media gravitates to male scientists and NGO spokesmen.

Institutionalization – Funding shifts to large environmental NGOs with male directors.

Sidelining – Women remain in grassroots roles while men handle policy negotiations.

Erasure – Histories credit policy shifts to NGO lobbying, not women’s blockades.

Replication – In climate justice, a similar split between grassroots women and male-led international forums persists.”

+

Conclusion.

My deeply personal journey — motivated by my late discovery of my (deceased) twin sister and my quest to expose falsified KSS adoption records — has led me to experience what I now understand to be part of a broader critique about gendered dynamics in activism. Despite my foundational contributions, including initiating critical research about one of the four major Korean Adoption Agencies — KSS — and serving as a key contributor to the KSS Adoptee evidence provided to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), I was systematically marginalized: falsely deprived of credit, excluded by a Korean Adoptee organization (DKRG), and omitted from a major FRONTLINE/AP documentary in which my influence was significant.

This experience reflects a disturbing but pervasive historical pattern: when women help build and catalyze movements, especially in their early stages, they are prone to being sidelined or erased — particularly once broader recognition, structure, or visibility enters the picture. I have discovered that my story aligns with a historically recurring phenomenon: men often assume leadership credit as causes gain traction, while women’s contributions are minimized, compartmentalized, or omitted. This dynamic underscores the importance of intentional, equitable practices that safeguard recognition and agency for women in collective movements. It also serves as a cautionary tale for the broader Korean Adoptee community, highlighting the risks and challenges inherent in Korean Adoptee activism.

At the end of the day, I haven’t quit — but I move forward with the hard-earned awareness that activism carries inherent dangers, ones that can threaten to destroy its very foundations.